How to Create Effective Social Scripts to Help Kids Prepare for New or Changing Situations

Social scripts can be powerful tools for helping autistic children understand what to expect in new situations. However, many well-intentioned scripts focus on controlling behavior rather than providing information.

This article describes how to create social scripts that truly support neurodivergent children.

“At school on Friday, there is going to be a special presentation. An OT will talk to my class. They will tell us about autism. I will sit on the floor with my friends. I will listen quietly. My teacher will give me a star if I do good listening. We will be so happy to have the OT come talk to us.”

I looked up from the booklet into the expectant face of the teacher.

When they told me they’d created a social script for a child in the class, this wasn’t what I wanted at all!

What Are Social Scripts?

Social scripts (also called social stories) are descriptive narratives that break down situations, concepts, or events into simple, understandable language to explain what to expect. They often include illustrations, photos, or other visual supports to enhance understanding.

They serve as informational tools that help people mentally rehearse and understand what typically happens in specific circumstances.

Purpose: Social scripts provide factual information about social environments, helping people understand unfamiliar or complex situations so they can feel more prepared and confident. They reduce anxiety about the unknown by making situations predictable and offering a reliable step-by-step understanding of what is happening as it happens.

What they describe

- The physical environment and setting

- Who is usually present

- What typically happens and in what order

- What other people are generally doing

- The usual atmosphere or tone of the situation

- Common variations that might occur

Key characteristics

- Written in simple, child-friendly language that’s easy to understand

- Use factual, descriptive information rather than rules or directives

- Focus on observable events and behaviors

- Provide a mental “playbook” for understanding situations

- Written from either first-person (“When I go to…”) or third-person (“When people go to…”) perspective

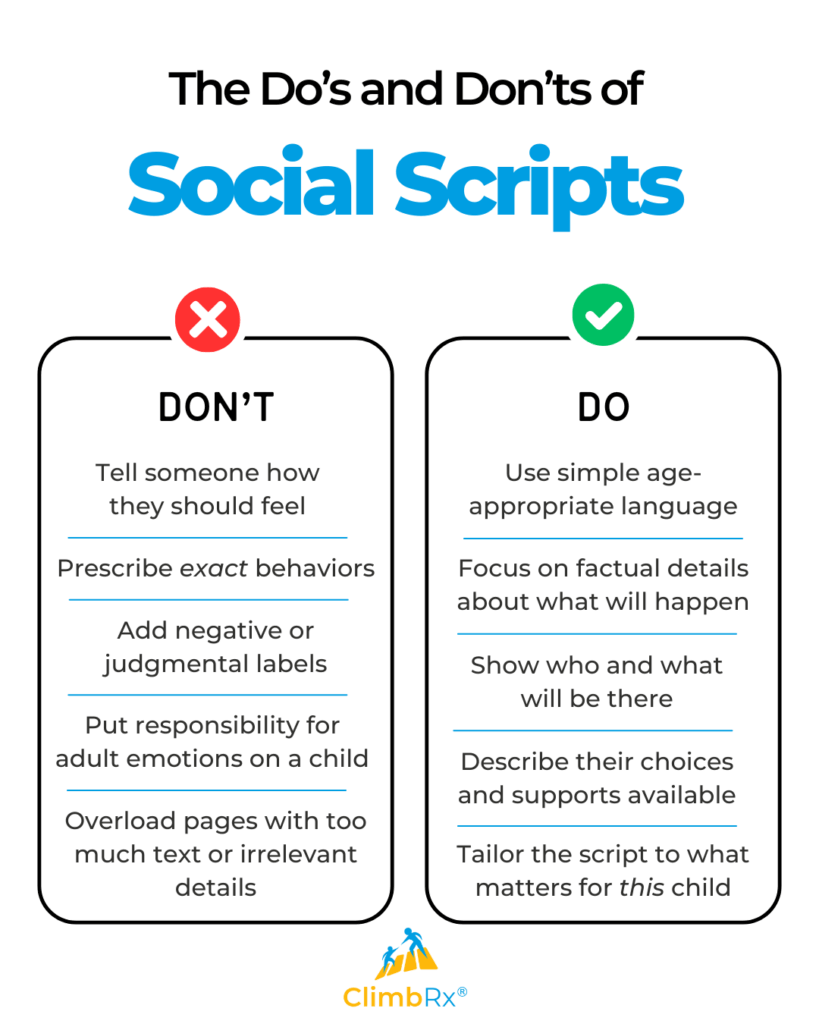

What they should NOT do

- Tell someone how they should feel

- Dictate specific behaviors they must follow

- Control or direct actions

- Make judgmental statements about right/wrong/good/bad behaviors

The goal is to provide clear, factual information so people can understand the situation, mentally prepare, and make their own informed choices about how to participate.

Social Stories vs. Social Scripts

While you’ll often hear the term “social stories” used to describe any type of narrative support tool, it’s important to know that Social Stories™ are actually a trademarked approach created by Carol Gray with specific formatting guidelines and criteria.

However, not all social scripts need to follow her exact format.

You can create your own personalized social scripts using your own pictures, language, and structure that works best for the specific child you’re supporting.

Are Social Scripts Only for Autism? Who Can Benefit from Social Scripts

While social scripts are widely known for supporting autistic children, they’re helpful for many different groups of people who benefit from understanding what to expect in various situations.

Children with ADHD often find social scripts valuable because they help with executive functioning challenges. When children with ADHD know what’s coming next and what the expectations are, they can better regulate their attention and energy. Social scripts can reduce the anxiety that comes from unexpected changes or unclear situations.

Children with anxiety (whether or not they’re neurodivergent) benefit from social scripts because they provide predictability and reduce fear of the unknown. When anxious children know what to expect, they can focus on participating rather than worrying about what might happen.

Children who are new to cultural contexts – such as those from different countries, children starting at new schools, or families navigating new social environments – can use social scripts to better understand new situations.

Children with sensory processing differences can benefit from social scripts that specifically describe the sensory aspects of environments, helping them prepare for and manage sensory input.

Any child facing a new or challenging situation can benefit from social scripts, whether it’s a medical procedure, family change, or new activity. The key is that social scripts work for anyone who finds predictability and information helpful for feeling more confident and prepared.

The most important factor isn’t the child’s diagnosis or label – it’s whether they benefit from having clear, factual information about what to expect in specific situations.

The Problem: When Social Scripts Become Behavior Control Tools

However, with the way that behaviorism has saturated adult/child communication in Western society—and even more so for neurotypical adults communicating with neurodivergent children—people have all too often slipped into a pattern of using social scripts to try to manipulate children’s behavior, not to provide children with crucial information.

Unfortunately, when you search online for social script examples, the vast majority focus on behavior control rather than information sharing. These scripts tell children exactly how they should act, how they should feel, and what responses are “correct.”

This approach is problematic for several reasons:

- It removes the child’s autonomy by dictating their emotional responses and behaviors rather than giving them information to make their own choices.

- It makes children responsible for adult emotions with phrases like “This makes Mommy sad” or “Teacher will be happy when you…” – putting unfair emotional pressure on children.

- It treats children as problems to be fixed rather than individuals who need information and support to navigate their world.

- It assumes one-size-fits-all solutions instead of recognizing that each child’s needs, interests, and coping strategies are unique.

- It prioritizes adult convenience over child understanding by focusing on compliance rather than genuine comprehension and comfort.

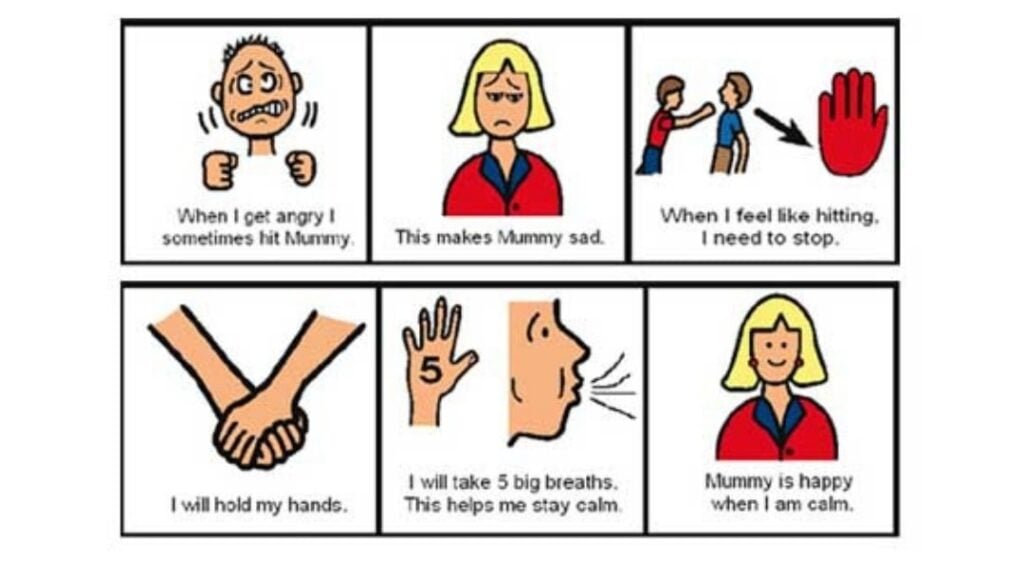

Here is an example of a behavioristic social script that demonstrates several of these problems:

This example shows many of the issues with behavior-focused social scripts. It tells the child that their emotions make ‘Mummy sad’ and that ‘Mummy is happy when I am calm’ – making the child responsible for managing an adult’s emotions. It dictates specific behaviors the child must follow (‘I will hold my hands,’ ‘I will take 5 big breaths’) rather than providing information about what options are available when feeling overwhelmed. Instead of helping the child understand their own needs and choices, it focuses entirely on producing the behavior adults want to see.

A good social script tells children what to expect, not how to behave.

Examples of Information-Focused Social Scripts in Action

In contrast to behavior-controlling scripts, here are three pages from an excellent information-focused social script.

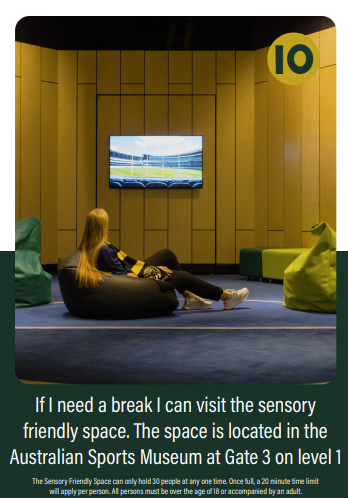

The Melbourne Cricket Ground (MCG) created a comprehensive sensory-friendly visual story for concerts that demonstrates many best practices for social scripts.

What makes this social script effective:

- It describes processes clearly: “I will open my ticket and scan the barcode to enter through the turnstiles” gives concrete information about what happens without telling the child how to feel about it.

- It explains why things happen: “Security guards will check my bag before I enter. They check everyone’s bag for safety reasons” provides context that helps children understand the purpose, reducing anxiety about the unknown.

- It offers options and supports: “If I need a break I can visit the sensory friendly space. The space is located in the Australian Sports Museum at Gate 3 on level 1” gives children autonomy by letting them know what choices are available.

- It uses real photos: Visual supports show exactly what to expect rather than cartoon representations, helping children mentally prepare for the actual environment.

- It focuses on facts, not feelings: Notice how this script describes what will happen without phrases like “I will feel excited” or “I should be happy.” It trusts children to have their own emotional responses.

- It provides practical details: Specific information like location (“Gate 3 on level 1”) helps children feel prepared and confident.

This is exactly what information-focused social scripts should look like – giving individuals the details they need to understand and navigate the situation successfully.

How Adults Seek Information vs. How We Write Social Scripts for Children

There are many situations in which adults try to ascertain information ahead of time in a situation.

For example, if you, as an adult, were going to visit a new beach, you might go online and look up where you’re allowed to park and how far the walk will be from the parking lot to the beach.

Or., when entering an enclosed activity like a zoo or amusement park, you might research whether you’re allowed to bring in your own food, or what kinds of food are sold in the park, and how much they cost.

When researching a movie or other entertainment option, you might look up its rating, why it’s rated that way, and if any content in it is going to be personally bothersome to you.

Imagine if you looked up a movie and were warned that it contains something you dislike, such as swearing, violence, or nudity, but then the warning went on to add, “You will sit quietly in the theater and keep your eyes on the movie. You will not be allowed to leave. You will feel so proud when the movie is done.”

You would likely and rightly think, ‘Excuse me? You don’t get to dictate whether I’m going to experience something that might bother me, and you certainly can’t tell me how I’ll feel about it if I do.‘

Imagine if you looked up a restaurant and the menu read, “You will pay $30 for a dish made of chicken, pasta, and tomatoes. You will eat all of it. You will say ‘Yummy!'”

You would likely and rightly think, ‘Wait, you’re telling me I don’t even get a choice of item from the menu? You can’t decide that on my behalf. Even if you do, you don’t get to decide how much of it I eat, and you don’t get to decide what my reaction is, either.’

These situations feel absurd because adults aren’t looking for laws, judgment, or shame when they look these things up. Adults are looking for details, information, choice, or autonomy.

They want to be able to make an informed decision, know what to expect, and understand the support or help available to them.

It’s the same for kids.

Kids want information in the right amount of detail for them. That’s what social scripts are intended to be when done well.

How to Write Informative Social Scripts – What Kids Need to Know

When creating your own social scripts, the most important thing to remember is that you’re writing for a specific child. What matters to one child may be completely irrelevant to another.

Think about what THIS child needs to know and what’s important to THEM.

Going back to the social script about my autism presentation that I mentioned at the beginning of this article, maybe some children would do fine with the information “On Friday…”

Meanwhile, other children would want something different.

That might be the time of day, “On Friday at 2 pm…”

Or, it might be the relative time of day. “On Friday, after we have reading time…”

It might be explaining what is different. “Instead of doing centers on Friday, we’re going to…”

Again, maybe some children would do fine with the information “an OT…” if they know what OT is. But otherwise, it’s just meaningless jargon, and this isn’t the time for a vocabulary lesson. Maybe “a person” is fine, or “somebody”, or perhaps you name the person and include their photo.

Think, what will actually give this child informative details?

Then, of course, all the behavioristic expectations simply need to go.

(Especially with the ultimate irony that it was literally during a presentation about autism!) There is no need for telling the child where and how to sit and listen, or that their teacher will give them a star.

Certainly, there is no need to tell them how to feel about the whole thing.

Essential Elements to Consider For Your Social Scripts

Timing and Schedule Details

- How much detail does this child need about when it’s happening?

- How is this different from a regular day?

- How is it the same as usual?

- How long will it last?

People and Environment

- Who will be there, and how should you describe them to this child?

- What does this child need to know about the space or setting?

- What does the space look like or sound like?

- What might be different about the environment?

- Are there any sensory considerations for this particular child?

Support and Choice Options

- What options does the child have during the event?

- What supports are available to them?

- Who can they talk to if they need help?

- What can they do if they need a break?

Activity Details

- What will happen step by step?

- What parts of their routine stay the same?

- What’s different or new about this situation?

What to Avoid in Social Scripts – Moving Away from Behavior Control

If you find yourself writing a sentence in a social script that describes a “bad behavior” (or a “bad choice”, or a “red choice”, or an “unexpected behavior”, or whatever words you might otherwise use to mean the same thing), you’ve gone down the wrong path.

If you find yourself writing “Sometimes I hit my friends…” or “I might want to scream and yell…” or “I am not allowed to run out of the room…”, you’re describing something that happens when a child is already actively dysregulated.

This isn’t the time when they want an informational menu that explains how the day is going to go. This is the time when they’re in crisis mode.

So, it’s entirely irrelevant to have on the informational handout in the first place.

What to Include Instead: Support Options and Helpful Details

Instead, your informational handout should:

- Describe what options they have: “My class will sit on the rug. I can sit on the rug or at my desk.”

- Tell them who can help them or what support is available: “My headphones are on my desk. I can wear them anytime I want.”

- Give details of specifics that are relevant to the child: “The presentation lasts 10 minutes. At the end of it, Mom will be here to pick me up. There will not be centers time on Friday. We will have centers time on Monday.”

When my family moved from America to Australia, I made a super-detailed breakdown for my son of what to expect as we traveled by two vans and three planes, through multiple layers of security and customs and baggage claims, across approximately 22 hours of time.

Included in that social script was exactly what type of planes we were flying on (Boeing Dreamliner!) and what height it typically flew at. Why? Because this was important and relevant to my son.

It was information he wished to know. It did nothing to manipulate his behavior or tell him how to act. He just cared about it, so it was in the social script.

Step-by-Step Guide: How to Write an Effective Social Script

If you’re trying to write a social script to support a child, begin with these principles:

- Write in the first person — e.g., “I” statements.

- Write with sentences that sound like the child’s level of language. If the child speaks with their mouth, do these sentences sound like something that could come out of the child’s mouth? If the child doesn’t typically speak, or you’re unsure what level of language understanding they are at, you can consider a peer of similar age or ability level, or simply try to write in simple, brief, direct sentences.

- Put only 1-2 sentences on each page or with each picture. Any more than that, and it starts to get very visually overwhelming.

Then, with those principles in mind, ask yourself:

- Am I writing about a situation the child has ever encountered before? How can I draw parallels to something familiar?

- If this is a brand-new situation, or a situation that’s changed for some reason, what is it that I expect is going to be different, unexpected, or tricky?

- What information does the child need to know to go through this experience?

- What information do I suspect the child will want to know, whether I find it important or not?

- What supports, help, or resources are available when things get tricky?

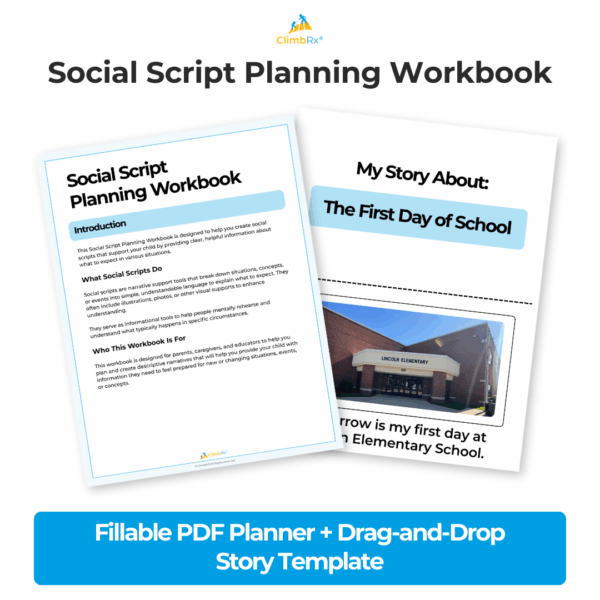

Free Download: Social Script Planning Workbook

Ready to put these principles into practice? Download our free fillable PDF workbook that will walk you through creating your own information-focused social scripts step-by-step.

This practical guide includes a drag-and-drop Canva Template to help you create your own social scripts easily.

Social Script Planning Workbook

A comprehensive planning workbook that you through creating social scripts step-by-step. This resource helps you plan, write, and design informational social scripts that help kids understand what to expect in new or changing situations. Includes fillable planning pages, review checklists, and a drag-and-drop Canva template to help you create your own social scripts easily.

Final Tips: Reviewing and Refining Your Social Scripts

Once you’ve created your social script, reread what you’ve written and check for any sentences telling the child how to feel or how to behave.

If there’s a way to rethink those sentences into information or supports, do that. (Maybe “I will sit and listen quietly” becomes “If I need to move around, Ms. Smith will help me go to a space at the back.“)

If there’s no way to rethink them into information/support, then remove those sentences entirely—they aren’t part of your social script.

Be wary of sentences that describe what the adult or the peers are going to be doing, thinking, feeling, or expecting. Sometimes, these can provide helpful information. But often, they are only barely-disguised behaviorism.

For example, “My class will go on a field trip. Some of my friends will pet the animals. I can join them if I’d like,” might be a helpful script. But “My friends want me to try and pet the animals. They will be happy if I give it a go,” is trying to manipulate the child with peer pressure.

Similarly, “My swim teacher will have games we can play in the pool together” is helpful information. But “My swim teacher hopes I can put my face in the water this time. They do not want me to be scared!” is attempting to manipulate the child by making them responsible for the grown-up’s emotions.

The Power of Information-Based Social Scripts

Social scripts can be invaluable methods of allowing neurodivergent children the opportunity to understand what’s going to happen before it happens, and to revisit it again and again because repetition often helps with understanding.

It should also give them knowledge of who and what will be available to help them, especially for situations that will be challenging for some reason. Consider yourself an ambassador to the child, sent to represent the school, therapy, or social situation.

How would you provide them information directly, understandably, and diplomatically? That’s the best way to write a social script.